Making Yourself Heard at the UPR — Writing a Stakeholder Submission

Engaging with the Universal Periodic Review can be a bit of a headache for civil society organisations. Here’s a speedy guide to getting your human rights concerns on the record.

James Marchant, Uproar

June 10, 2019

As human rights defenders and advocates, UN institutions and human rights mechanisms are fundamental to a lot of our work. These institutions are meant to uphold the human rights standards underpinning the global order, and serve as an instrument to hold rights abusers to account on the world stage. But when it comes to listening to the experiences of global civil society, they sometimes fall a little short.

For starters, these processes are often pretty impenetrable — as an advocate, it’s often really difficult to know where you can influence them, and who you need to engage with. But this doesn’t need to be the case.

The Universal Periodic Review — a global human rights peer review process (read more about it here) — is particularly useful because it gives human rights advocates the chance to share their experiences and contribute evidence to the international community, and help states to make decisions about their human rights priorities for the review.

Today, we’ll show you how to make a UPR stakeholder submission to the OHCHR (that’s the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights).

This is a really important step for organisations to take to get their issues on the map, and to make sure that diplomats are equipped with all the latest human rights information to help them decide which issues to tackle at the UPR.

Let’s run through the process quickly.

So where does this sit in the overall UPR process?

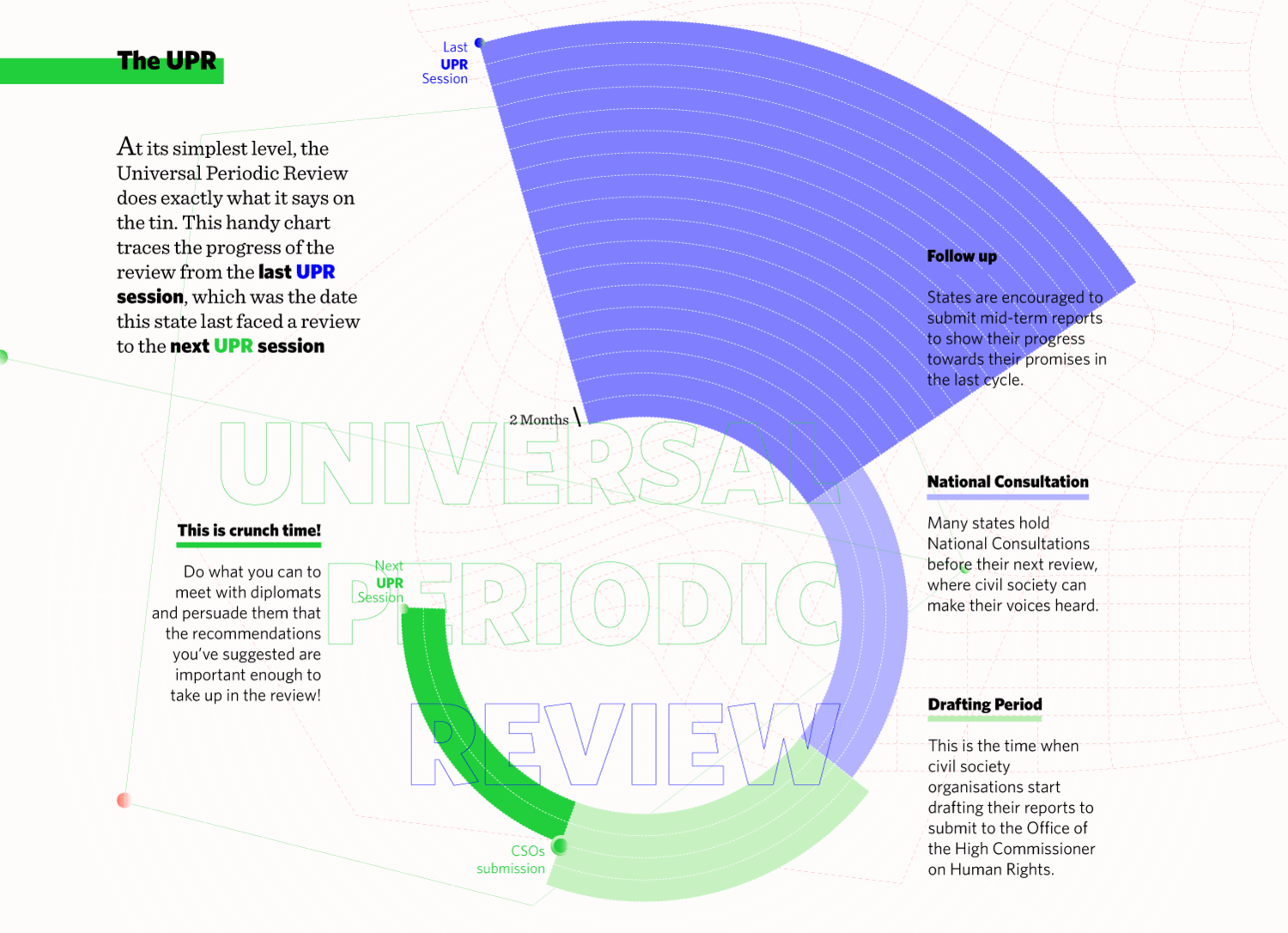

An overview of the primary ways civil society organisations can engage with the UPR across a full cycle.

Making a submission to the OHCHR happens right at the start of ‘crunch time’ — the intense period where civil society organisations lobby diplomats to make specific recommendations to states being reviewed.

It comes at a time towards the end of the UPR cycle where you should have plenty of evidence and information about the state under review’s (or SuR) human rights record over the past few years — evidence that can help inform diplomats about which human rights challenges need to be addressed most urgently.

Who reads the report, and why is it important?

The way the UPR works, every country is able to review the human rights record of every other country in the world every five(ish) years. That’s a lot to keep track of, and many foreign ministries — especially in smaller states — can’t be expected to stay on top of every single human rights-related development globally. They need help.

Ahead of the review, three reports are published to inform diplomats about the human rights situation in the SuR. they are:

1. National Report

This 20-page report is written and published by the state under review. As you might expect, the National Report often paints a rather rosy picture of a SuR’s human rights achievements over the preceding five years.

This isn’t to say it’s not of legitimate value — states often have a lot of good data on a broad range of human rights issues. But national reports are prone to omission, exaggeration and outright deceit from certain quarters, as states attempt to present a sanitised version of their human rights record to the international community.

As a result, diplomats generally place more weight on the other two reports available to them — the UN Report and the Other Stakeholders Report.

2. UN Report

The second report is the UN Report, compiled by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on the basis of information produced by UN organisations and institutions, including treaty bodies, special procedures, and other relevant UN documents.

As a result, this report offers largely substantive information about the human rights situation in the SuR. But UN institutions can’t capture all the insights from the ground, and for diplomats to reach an informed decision about human rights priorities, extensive information is required from civil society stakeholders working on the frontline of human rights struggles.

That’s where the third report comes in.

3. Summary of Other Stakeholders Report

It’s awkwardly named, but this report offers a key opportunity for activists and advocates to exert influence over the UPR process. Around 6–8 months before the review itself, civil society organisations are invited to submit their own assessments of the SuR’s human rights record to the OHCHR.

These reports aren’t shared directly with diplomats — rather, the OHCHR compiles all of the civil society reports together into a single summary report offering an overview of the SuR’s human rights record. If your human rights reports are well-documented, properly referenced, and well constructed, then you can expect a handful of your key priorities to make it into the final OHCHR report.

Any civil society organisation can submit a report — you just need to register on the OHCHR platform, fill out some basic information, and submit your report.

What does a civil society report look like?

That depends on a couple of things.

First off, is your organisation submitting information by itself? Or as part of a coalition of organisations? On a practical level, this affects the amount of space you have to make your arguments:

A solo submission has a word limit of 2815 words.

A joint submission has a word limit of 5630 words.

So if you’re trying to capture a lot of information about a state’s human rights record on a particular issue, it’s often best to do it as part of a joint submission. But the benefits don’t stop at just being able to say more — submitting a report as part of a coalition of organisations also helps signal to diplomats that the evidence submitted is reliable and credible, and lends it more legitimacy.

Besides length, there aren’t too many rigid guidelines about how your submission should look. Here are some things to bear in mind, though:

- Coordination is key! — In many countries, coalitions of human rights organisations will coordinate and distribute their work to deliver submissions on a number of key thematic areas.

Often a coalition will group together to make a submission on the general human rights situation in the SuR, and then sub-groups of organisations from the coalition will also submit separate in-depth reports on particular topics, such as digital rights, LGBTQ rights, the situation of refugees, or women’s rights.

This helps to provide diplomats with both breadth and depth of information, and also shows that civil society is united and in agreement over the leading human rights challenges in the SuR.

Coordinate your submissions! A little teamwork goes a long way.

- Hold states to their promises!— It’s usually helpful to start your submission by referring to the commitments made by the SuR at their previous review. You can find details of past recommendations to the SuR on the UPR-Info Database

By providing an explanation of where the SuR kept its pledges — and where it flunked on them completely — you can help inform diplomats about where states should be commended, and where they should be held accountable for their failures.

One of the main purposes of the UPR is to create obligations for your target state. So make sure to hold them to their UPR pledges in the period after their review.

- Speak the right language — The UPR runs the full gamut of human rights-related issues, and so it’s important that you structure your ideas clearly and effectively, and use the correct human rights language so that diplomats know exactly which issues you’re talking about.

When you do this, it’s usually best to tie your comments clearly to rights established under UN conventions. For a lot of topics this is straightforward enough, but if you’re talking about an unconventional human rights subject like digital rights you need to be mindful to speak the right language.

For instance, if you want to talk about state-directed online censorship, organise your evidence under the heading ‘freedom of expression’ — a protected right under the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. Or if you want to talk about the harassment of women online, make reference to gender-based violence — a human rights violation explicitly addressed by the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the 1994 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.

Watch out! If you don’t frame problems in the proper human rights language, diplomats may not get the message.

Still finding it hard to know what you should be submitting? Here are some good examples of reports other organisations (and coalitions) have submitted to the OHCHR — you can’t go too wrong if you use these as models for your reporting:

It’ll take a little bit of your time to get things ready, but submitting reports to the OHCHR is a really important way to deliver evidence of human rights abuses to the international community, and inform states about the kinds of recommendations they should be prioritising during the UPR process.

We hope the hints and tips above help you along the way, but if you need more information about submitting reports to the OHCHR don’t hesitate to get in touch at hello@uproar.fyi!